Woodland Journeyman, Jon Jewett, completed an apprenticeship with the Wildlife Trust last year. He has some really interesting and insightful views about woodland and wildlife that we felt would be of interest to readers.

In this Woodland Journeyman mini series, Jon will be explaining – based on what others have taught him – why sometimes trees need to be cut down, a case study of good practice in woodland management on the Island and finally explaining the current issues with Ash Die Back. Ed

Public Service Announcement – I cut down trees to save the planet.

Now this will take a little bit of explaining and a few slides, so please bear with me.

It’s good to see the uproar caused by destruction of habitat on the Island, but it may not be as simple as it might first appear.

Not every tree is sacred. Not every tree is great.

Hopefully I’ve got your attention, so please sit back and enjoy the tale of two woodland schemes on the Isle of Wight. I think they might shed some light upon the matter.

The JIGSAW Planting scheme

Back in the early 2000s the Forestry Commission, along with their partners, rolled out the JIGSAW Planting scheme. It provided funding for landowners to plant up agricultural land with new trees to connect existing ancient and semi-natural woodlands.

The Island was the largest community to take up the project, with our unique isolated biosphere, a healthy population of red squirrels, lack of browsing deer, and limited workable agricultural land. Additional funding was directed here as the project uptake diminished across the rest of the country.

Variety of plantings

Some plantings were community-led (schools, recreational spaces and what not) others private, but all focused upon creating corridors of travel for isolated populations of red squirrels and dormice. Hazel, oak, Scots pine and a variety of pioneer species were on the menu.

All schemes, and in fact all woodland require a long term management plan to remain viable. Maintaining the status quo is not an option.

Planted and left

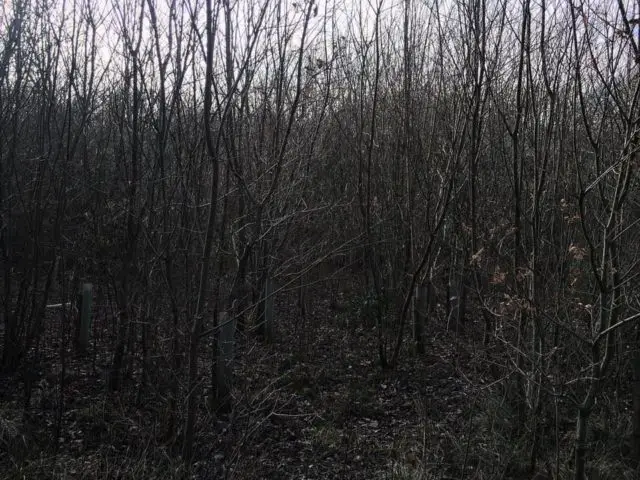

These images showcase one small planting block that received no further management until this winter – 16 years after it had been planted. Once the trees were planted and the woodsmen walked away, the willow moved in and colonised the unmanaged ground.

Click on images to see larger versions

They proved hugely successful. As a pioneer species they did exactly what they evolved to do. Unfortunately this was to the detriment of the newly planted saplings.

Many not able to keep up with the vigorous growth rate of the natural colonisers, perished and died as the canopy closed in and shadow descended upon the land.

Can take 1000s of years to play out

Now this is all part of the natural process, but it really does take hundreds, if not thousands, of years to play out.

Willow will dominate a landscape void of its natural predators.

In the natural cycle of things, browsing herbivores or the mighty beaver would open up that canopy for further flora to capitalise on the space.

Carving out their own footprint

Maybe a birch or poplar, with their accelerated growth rate, will shoot for the sky, able to get that little bit taller and carve out their own footprint, whilst wrapped in a protective blanket of brambles.

Then there’s the oaks, nestled amongst the blackthorn where a Jay has purposefully planted a stash of acorns for future consumption.

Like a nursery, they’re protected from those ungulates as they slowly plod upwards, watching the amateurs burn bright but brief, lacking the structural integrity of slow purposeful progress.

And everything else

There’s so much more going on, the gradual build up organic matter, the mosses, the lichens and fungi, all preparing the way for others to tap deep and bring more nutrients to the surface.

The plethora of flora that are agoraphobic but still require sunlight, at least some of the time. The ones that really are useless at spreading their own seed unless hoovered up by a boar and pooped back out again in freshly pawed ground. And the ones that are patient as hell and will wait until that big old oak comes crashing down to burst into life in an oasis of sunlight.

A complicated rich tapestry

It’s a rich tapestry that’s far more complicated than we could ever imagine. Constantly changing in very subtle ways over immense periods of time.

Woodland management is about replicating these changes to speed up this process and to replace that interaction of flora and fauna where humans have eradicated these keystone species.

Look out for part two in the Woodland Journeyman’s mini-series, where he talks about an area of woodland that showcases good practice. Ed