Jonathan Dodd’s latest column. Guest opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication. Ed

I’m often surprised by things I remember. There are things I remember vividly, and I suspect I always will. And other things I think I might sort of remember, which do reappear when I concentrate, perhaps very slowly and gradually, like squeezing tomato paste out of a tube. Sometimes I’m sure I’ve forgotten, but some trigger pulls it back. And there are things that take ages to remember. And there are all those things that I don’t remember at all.

I’ve often wondered how the whole thing works. Some people remember things with a frightening efficiency and detail, and I know some people who have what appears to be a random memory access, which varies from day to day. I know people who can manufacture memories, and I can never be sure whether they do it deliberately or unconsciously. Anyway, how do we know if we’re remembering, or just making it up?

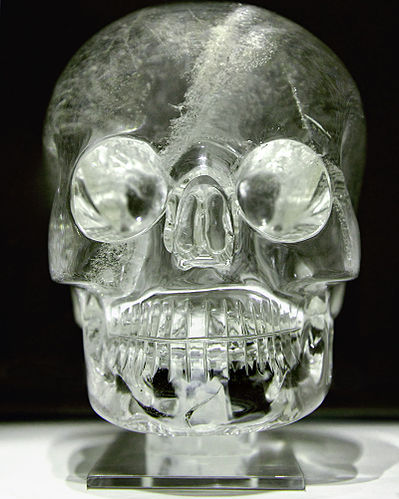

A large light-filled space inside their head

I was once on a course where things like this were being explored. We were each asked to think of some memory and then describe the process of remembering. It was very interesting. I remember one person who imagined a gigantic crystalline structure in a large light-filled space inside their head. They were able to send shards of light into the centre of it and retrieve almost anything at will. It was amazing. I never worked out whether they had always filed things in a structured way, or whether their brain just worked like that.

Another person had an elaborate system involving archers, writing questions on pieces of parchment, attaching them to arrows, and sending them across a chasm. These arrows were picked up and read by archers on the other side, who scurried off to a maze of monastic cells, looking for scrolls with the answers on. Eventually they would find them, and the answer would be sent back over the chasm via another arrow. Needless to say, this person’s memory was not too speedy and sometimes the memories retrieved were a bit scrambled.

No wonder it wouldn’t work

I know these are colourful examples, but everyone had a different system, or at least the system they imagined was different, and their recall seemed to reflect their method, and the method seemed to fit the sort of person they were. I tried for years to install a giant crystal inside my head, but I never managed it, and I’ve only just realised why. I forgot that you need a seed for your crystal to grow on, like copper sulphate in a beaker in the school gym. Silly me. I got stuck on finding a hole big enough to push it in, rather than growing it inside. No wonder it wouldn’t work.

My memory works in strange ways. For instance, I haven’t used the term ’copper sulphate’ for decades, and I honestly had forgotten everything I learned in Chemistry at school. Or, rather, I hadn’t used any of it. And yet, while I was writing about crystals, I knew instantly what those big blue things were made of. I have no idea how that happened. Especially since I can’t remember the name of that actor who was in that film I watched only the other day, it was about a man in a car and the wind was blowing and someone else was in the car and the sun was setting and I can remember everything about it except his flipping name! How does that work?

Maybe it’s just the retrieval system that gets creaky

Memory is a frustrating thing at the best of times. You remember things you wish you could forget, and vice versa. People say your memory gets worse as you get older, but they don’t say when that is. I worry about my memory going all the time, especially when I can’t remember the names of actors, but then I’m reassured because I just remembered copper sulphate. It’s a mystery. I think we do remember everything, somewhere. Maybe it’s just the retrieval system that gets creaky.

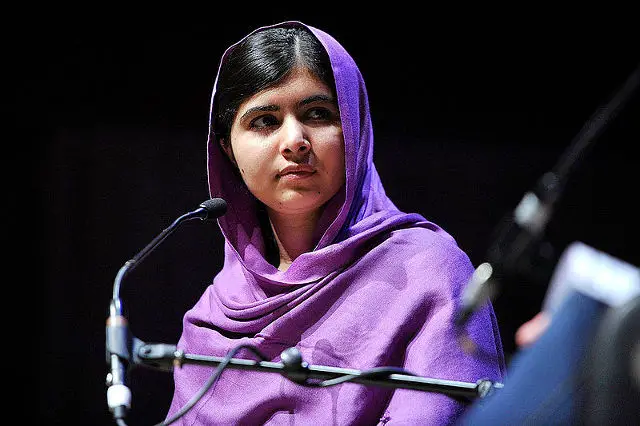

Another thing about memory that intrigues me is the relationship between who we are and what we remember and how we’ve been affected by our life experiences. We do change, growing or receding depending on our circumstances, and our successes and failures. Who doesn’t feel like they could jump mountains when they fall in love? And who doesn’t feel like they could slither down a wormhole when they’re betrayed by someone close? Sometimes memories leave big shadows of various hues inside us.

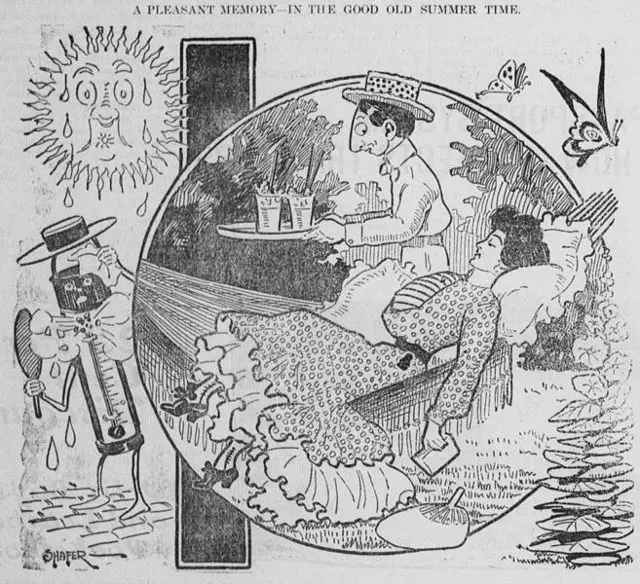

The memory remains the same, but different filters are available

Most of us think that memories are fixed. All that really happened, there’s a movie of it in our heads, we can’t change it. We really believe this. But it’s more complicated than that. Our memories are affected by our mood when we remember them. The joy of a smart outfit or new dress can be destroyed in an instant by spilling something on it or discovering that someone else is dressed identically – or better. Optimists remember the joy and discount the despair. Pessimists do the opposite. We have a choice in how we remember things. The memory remains the same, but different filters are available.

The ability to change these memory filters is vital to all of us. How otherwise would we ever get over the loss of someone we love, or some other disaster? In time, we adapt the way we perceive our memories, and there are ways to help that along, thank goodness. I can remember times in my life which I wouldn’t like to find myself in ever again, but I revisit them now with a degree of distance, mainly because I’ve survived and my life has closed over them like scar tissue over a cut. We’re designed like that.

It’s not lost, just mislaid

So how do we deal with these pesky memories, and how do we help ourselves not to let anything slide under the surface so we think it’s lost and gone for ever? I think the most important thing is to remember that we don’t forget anything. If we think we’ve forgotten something, we must remind ourselves that it’s just the archer’s lunchbreak, or the lights have gone out, or the book got put on the wrong shelf in the wrong room on the wrong floor. It’ll turn up eventually, it’s not lost, just mislaid.

Besides, how do we know we’ve forgotten anything? We have to remember at least part of it to know that we can’t remember, obviously. Sometimes it helps to imagine a better retrieval system. Instead of thinking about how it works now, you could redesign the whole thing. Do a spring-clean. Replace the archers with those vacuum-tube things they have in shops sometimes. Or install some state-of-the-art computing equipment. Or start labelling your monk’s cells and colour-coding your memories so you can track and store them easier. What would work best for you?

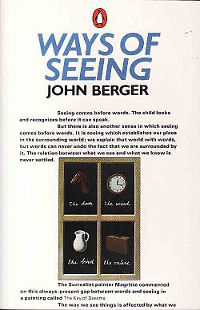

Our memories aren’t a single layer, like a reel of film

I also believe that our memories aren’t a single layer, like a reel of film. Just like a multi-track recording, we reassemble our memories from different elements. There’s the bare facts memory, and our emotional involvement memory, and other tracks, perhaps because the memory involves someone else, so we weave in our feelings about that person, and there may be a background track or two, that creates a juxtaposition. For instance, we can remember how we reacted to 9/11, or we can remember where we were or who we were with, or what we were doing at the time, and frame the event inside that.

We also remember things through different senses, like different instruments in a band. There’s everything we saw, and everything we felt physically as well as emotionally, and there’s the actual soundtrack at the time, and there’s a record of all our thoughts at the time as well. Some of us remember one or more of these almost exclusively, or have difficulty summoning one or another. For instance, I don’t have the capacity to remember visually, so I have to reconstruct everything from the other strands.

Make sure that we find the particular version we’re looking for

After all that, when we remember something, that remembering gets added to that memory, and the way we react to the memory gets added too. Sometimes we reconstruct the memory to make it better, or less frightening, and we’re capable of telling ourselves that this version is true.  And sometimes our memories become part of our dreams, which can muddy the waters even more. But our brains are clever, and they can tell the difference. Along with the effort to remember things, we have the ability to make sure that we find the particular version we’re looking for.

And sometimes our memories become part of our dreams, which can muddy the waters even more. But our brains are clever, and they can tell the difference. Along with the effort to remember things, we have the ability to make sure that we find the particular version we’re looking for.

It’s no accident that one of the foundations of our justice system is the idea of ‘the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth’. Police investigations and court cases are designed to extract the actual truth from all the accidental or deliberate fuzziness surrounding our memories. If we’re searching for it, we can always find that timestamp that tells us which version it is.

Turn that memory into something bearable

In life, we don’t need to stick with the original memory in all its absolute exactness. Sometimes we need to tamper a little with our recall because of the nature of the experience. If you have a horrible memory that haunts you, you can tweak it a bit, by maybe substituting the original soundtrack with some completely inappropriate piece of music, or changing something else, whatever works for you. It might feel different when you do that, and it might make it feel less threatening, and you might be able to add that to your memory store, and gradually you’ll be able to smooth off the edges and sharp corners, and turn that memory into something bearable.

There’s more than one way to train your memory. You can’t change your memory of the original experience, but you can experience your remembering differently, as long as you remember the difference. It can help a lot, and sometimes it can bring you peace of mind too.

If you have been, thank you for reading this.

Image: xlibber under CC BY 2.0

Image: Jem Stone under CC BY 2.0

Image: Rafał Chałgasiewicz under CC BY 2.0

Image: lars_p under CC BY 2.0

Image: public domain under CC BY 2.0

Image: Lewis Clarke under CC BY 2.0

Image: Loozrboy under CC BY 2.0

Image: Fair use

Image: Southbank Centre under CC BY 2.0