Friday was market day in Totnes and in spite of the rain the streets were teeming. The fishmongers, the soap makers and the bakers were doing a brisk trade and the high street's three butcher's shops were packed.

The small Devon town of 8,500 people has never really been in the headlines in its near 1,000-year history. The Norman castle has never been the scene of great battles or sieges and the town huddled on its southern slopes has quietly prospered, avoiding the envious eyes of brigands and raiders.

But this weekend the citizens of Totnes are celebrating victory in a rare battle which has grabbed the attention of the country. The town defeated the attempts of the high-street chain Costa Coffee to open a branch and dilute the charms of their independent and colourful high street.

Pruw Boswell, the mayor, was jubilant but slightly tired after her breakfast show interviews. "You don't mess with Totnes," she said, as her husband placed her mayoral regalia over her head in preparation for an official engagement. "It might seem like a quiet place where you can roll in and do what you want, but we have shown Costa that we are the mouse that roared."

Cafe owners were happy that a threat to business has been removed, while citizens enjoyed a local victory. Tony Kershaw, the owner of La Fourchette, a high-street cafe and restaurant, said everybody was pleased at the news.

"There was a definite split in the town, but even people who wanted Costa to come would say that deep down they were pleased with their decision. Although Costa are probably better than most, they still produce a generic coffee. They are the McDonald's of the coffee world, the lowest common denominator," he said as he laid out cakes on his counter on Friday.

Costa Coffee, Britain's largest cafe chain, with twice as many outlets as Starbucks, announced its plans to open in Totnes in May and has faced widespread opposition since. Totnes High Street has a Superdrug and WH Smith, but the vast majority of its shops are independent retailers, a sight rarely seen in Britain today. It also has 42 places which sell coffee, ranging from a hotel to vegan and Middle Eastern cafes.

"We have a tradition of independence and a history of being different. We had to protect the special ambience that visitors enjoy and stop Totnes from becoming just another 'clone town,' with identical shops and cafes" said the mayor.

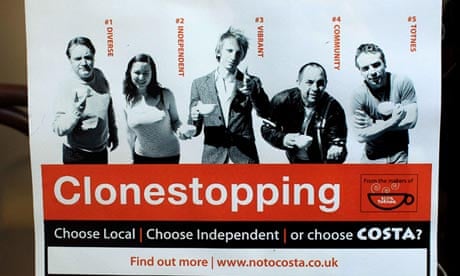

Costa outbid local businesses for a prime lease and boasted of its successes in overcoming local opposition. But Totnes was not deterred. Citizens set up a campaign with a website, notocosta.co.uk, with stylish Trainspotting-style posters. Almost 6,000 people signed a petition and around 300 wrote to the council to object. But South Hams councillors agreed to Costa's application.

There was nothing to stop Costa opening, but its directors agreed to a suggestion by the local Conservative MP, Sarah Wollaston, to visit Totnes and meet local representatives.

Three weeks ago Chris Rogers, the new managing director of Costa, and two fellow directors arrived at the Totnes Conservative Club, an imposing two-storey building in two tones of blue.

One of the directors began what witnesses described as a "well-oiled" presentation. He told the residents he was not there to placate or persuade them – before trying to do exactly that. He told the meeting of the benefits a Costa cafe could bring. Costa would not threaten existing coffee shops and would add to the vibrancy of the town. The residents had no need to worry about other companies following in the wake of Costa because they would not like the kind of properties available. The new Costa cafe, he said, would provide a place where people could come together. At this point his audience burst into laughter at the director's clearest demonstration of lack of local knowledge.

The representatives explained to the Costa directors how it could damage the local economy and compromise Totnes's tourist charms.

Last week, Costa arranged to meet Wollaston at the House of Commons. "When they asked for the meeting I feared the worst, but I was overjoyed with their decision. This was not a campaign against Costa per se, and I think other companies could take a leaf out of their book," she said.

Rogers said Costa had recognised the strength of feeling and taken into account the specific circumstances. "Totnes is a town with a long and proud history of independent retailers. It has one of the lowest percentages of branded stores of any town of its size in the UK, very few empty shop fronts, as well as a very high proportion of places selling coffee," he wrote in a letter also signed by the mayor and the MP.

Frances Northrop, head of the local community development organisation, who attended the meeting, said she was surprised Costa had withdrawn. "I thought it was inevitable. When a company has an expansion policy, it's quite unusual for the community to intervene. The interests of communities and big business are at cross purposes," she said.

She explained that the opposition was not based on snobbery or aesthetics, but on an understanding of the local economy. "We have brought together a lot of local producers and retailers and we know a lot about the local food economy and how strong it is and also how fragile it is," she said.

"When Costa put in their planning application, it was obvious the threat to local business was massive, not just the coffee shops but their suppliers as well. It is the nature of Costa that they offer standardised products produced at centralised factories. This is how they drive down their prices to maximise their profits.

"We want to keep money circulating locally. We support family businesses that use a local IT company, buy their food locally. Obviously they don't get their coffee locally. They are also a family to their staff. They spend their money locally where they live and they send their children to school. It seems like a good system; that's the beauty of our high street. It's got more independents than chain stores and that's part of its charm to visitors," said Northrop.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion