Could these five projects improve life in the UK?

- Published

The government is pressing ahead with the HS2 high-speed rail link between London and the North of England, but there are critics who believe the money could be better spent elsewhere.

But what are the alternatives? Here are five other infrastructure projects, suggested by experts. Another five will follow tomorrow.

Some are much smaller, some represent blue-sky thinking and some are every bit as ambitious in scale as HS2.

Welwyn North tunnel

A train crosses the Digswell Viaduct in 1938

It may not be as sexy as a country-spanning high speed rail link, but users of the East Coast Main Line might see palpable benefits from tackling one of the rail network's most problematic bottlenecks, near Welwyn North in Hertfordshire. The line narrows from four tracks to two as it passes over the Digswell Viaduct and through a series of tunnels. Despite being just four miles, the narrow section has a big knock-on effect for trains up and down the line. If an inter-city train finds itself behind local traffic it can't simply overtake as on most of the line. It must wait or go slowly. A four-track tunnel and viaduct would have a big impact on punctuality for all destinations on the East Coast Main Line and cost relatively little, rail experts suggest. In the 1990s such a plan was announced, external. But the project was killed off with Railtrack's demise.

Cost: £440m estimated (New Economics Foundation)

Likelihood: Probable, at some point

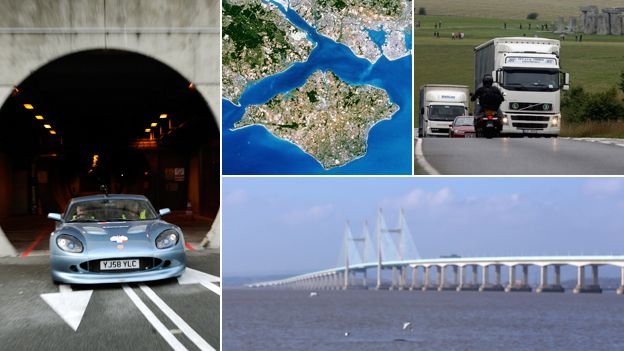

A motorway for the east

There are north-south motorways up western England - the M5, M40, M6. The M1 goes up the centre. But east of that is nothing but the A1, which is motorway only in parts. "There's definitely a bias to motorways taking you west to go up north," says Paul Watters, head of transport policy at the AA. One plan could be to expand the M11 up from Cambridgeshire to Lincolnshire and the North East. But building brand new motorways is out of fashion. A more realistic option would be to upgrade the A1 to motorway all the way along, Watters says. The most pressing need for improvement is the section north of Newcastle serving the east coast of Scotland, he says. It is currently a mix of single and dual carriageway. Another eastern option is taking the A14, which runs from Felixstowe to the M6, and turning that into motorway, says Jack Semple, policy director at the Road Hauliers Association. Then there's the A12 from Brentwood to Suffolk.

But road widening of any kind is hugely contentious for environmentalists. It is also expensive. When the government announced in 2002 that it was widening a 29-mile section of the A1 to three lanes, the price tag was £263m. Scaling that up crudely over the course of the entire A1 would suggest the cost could even run into billions. Sian Berry, the Campaign for Better Transport's roads campaigner, says widening the A1 is "hugely expensive" and unnecessary. "There are much better choices for spending billions of pounds. Building wider roads in the long-term just causes them to fill up and encourage more car traffic."

Cost: Billions

Likelihood: Small widening projects likely but overarching motorway plan unlikely

Bridge to the Isle of Wight

A hardy perennial of life in the Isle of Wight is the suggestion that a bridge to the mainland would be a good idea. Many Isle of Wight residents joke that the island has the most expensive ferry crossing in the world by mile. A return trip with car and two adults can come in at over £100 during high season. The frustration was summed up by a letter writer, external to the Daily Telegraph: "Every other island community in the British Isles which had the feasibility of a bridge has seen one built. Why is there no bridge to the Isle of Wight?" Supporters of a bridge argue that even a toll-based crossing would produce competition that would push prices down. They also suggest that the island could get an economic boost. George Bristow, who campaigns for a link with the mainland, says "the economy of the island is dying". He argues a bridge would give the island a 30% increase in GDP. The bridge should link with the A3(M) on the mainland and connect with the east side of the island, he says.

The Isle of Wight Party was set up to campaign for a fixed link with the mainland, whether bridge or tunnel. Tunnels are expensive. As a rule of thumb a rail tunnel of about 10m in diameter costs about £30m per kilometre, says Bill Grose, former chairman of the British Tunnelling Society. Bridges are cheaper. The road bridge to the Isle of Skye opened in 1995. But it too was controversial. It cost a total of £39m to build, external under the Private Finance Initiative, £12m of which came from the government. In 2004, the Scottish government bought the bridge from its private owners after public criticism of what was said to be the highest per mile toll, external in Europe.

Many Isle of Wight residents are against a bridge. And an OFT report in 2009, external into ferry fares found they were "not obviously out of line with other commercial ferry services across Europe". And then there is the issue of squirrels. A bridge might allow grey squirrels in to wipe out the island's population of red squirrels. Red squirrels on the mainland have almost died out. But up to now the Solent has acted as a natural barrier to their grey cousins.

Cost: Unclear

Likelihood: Not on the immediate horizon

A new Channel tunnel

Would a direct road tunnel be better than the Eurostar or Le Shuttle?

If blue skies thinking is allowed, there is no bluer option than either a road tunnel under the Channel or a bridge over it. Bearing in mind the cost of the original privately funded tunnel many politicians would have kittens at the thought of financing another one. But before the rail tunnel under the Channel was chosen back in 1986, there were three other proposals on the table, all involving road links. Some say this would make more sense. Drivers could just speed between France and the UK without needing to get out of their car and on to a train. "As a motoring organisation we'd prefer a free-flow system of drive in, drive out." says Watters.

The challenge for a road connection is gales on a bridge and exhaust fumes in a tunnel. "Road tunnels need much more ventilation than rail tunnels and so there is a technical challenge there," says Grose. "You'd probably need a mid-Channel ventilation island." What about the route? "Difficult to say whether to go to France or Holland," he says. "If the former it would relieve the rail tunnel, if the latter it would replace ferries." One of the original proposals suggested a tunnel between artificial islands approached by bridges, Watters says. If the bridge held a tube protecting cars from gales - as the original bridge plan envisaged - then that might be feasible.

But is a second tunnel needed? The freight industry says no. "There's plenty of spare capacity in the existing tunnel," says James Hookham, managing director of the Freight Transport Association. The government is due to examine capacity in 2016, Watters says. And it's no good just thinking about now. We need to be planning for 20 or 30 years time, he argues. It means starting on the planning soon. But he doubts it will happen. The first tunnel cost billions. Today, with one tunnel already, such a cost looks excessive.

Cost: Many billions

Likelihood: Minimal

Trams for Liverpool and Leeds

Liverpool had a tram system until 1957

Trams would be a "much more equitable" way of helping the regions than HS2, says rail expert Christian Wolmar. Left-of-centre think tank the New Economics Foundation is backing tram schemes, external in Liverpool and Leeds as part of its alternative plan to HS2. David Theiss, author of the report says that for every pound spent on HS2 the taxpayer will get back between £1.20-£1.90. In contrast the Leeds and Liverpool trams - each price tagged £1 billion - would give a return of between £2 and £3 per pound spent. Quality of life in these cities is more important to boosting their economies than cutting inter-city journey times, Theiss argues. Trams have key advantages. They are seen as a pleasant way to travel. They take the pressure off the road network. And they attract more users than buses, he says. But trams are not always a badge of honour for a city. Edinburgh's tram has proved controversial and expensive. Campaigners say the scheme is arriving years late, external and has cost £776m.

Cost: £1bn each for Liverpool and Leeds (New Economics Foundation)

Likelihood: Might happen, but timing unclear